Despite its low profile, the country’s pearl industry stands accused of providing revenue to help prop up the military junta

TANINTHARYI, MYANMAR – For the controversial pearl industry in Myanmar, it’s business as usual in the southern Myeik Archipelago, despite calls for international pearl farming companies – including the Japanese – to exit the country after their businesses were accused of generating revenue for the military regime fighting a civil war against its citizens.

In a well-known Burmese song Myat Thwel, or Weeping Eyes, Khin Maung Toe sings “My dear, pearls are the tears of oysters, so don’t adore them on your neck.”

His song implies the man’s wish for his girl not to wear pearl jewellery because it is associated with the mass killing of oysters, making many of his audience lose their fondness for pearls.

Source: Mapbox

With Myanmar transforming into a war zone since the 2021 coup d’état, there is a growing sentiment that people are akin to the oysters shedding tears, as the pearl production industry stands accused of fueling the finances of the military responsible for the killing and torture of civilians.

“Now it goes beyond the tears of oysters. The military is using the revenue generated from the pearls to buy arms and ammunition, against the people’s will,” said Aung Myint*, a resident of Myeik Archipelago in Myanmar’s southern Tanintharyi region, the country’s hub for pearl farming.

Numerous human rights groups have called on pearl companies to exit Myanmar – mainly targeting Japanese pearl company Tasaki, whose subsidiary Myanmar Tasaki Co Ltd produces the largest share of pearls in the country.

Human rights group Burma Campaign UK added the company to its “dirty list” in March 2022. The list names international companies doing business with the Myanmar military or involved in projects that violate human rights or destroy the environment.

According to a recent report by the MEGGA Initiative, a civil society group that works for social and environmental justice in the Tanintharyi region, Myanmar Tasaki operates pearl farms in Domae and Langan islands in the Myeik Archipelago. Its pearls are claimed to be sourced “ethically and sustainably.”

The report also highlights the fact that the pearl farms overall have expanded since the coup – driven by the operation of foreign and local companies and the increasing global demand for luxury items. Recently, local enterprise Virgin Pearl won a tender to develop a pearl farm on Kaw Ye Gyi island.

So far, none of the companies have announced an exit from Myanmar. This can be linked to the fact that Myanmar’s pearl industry has been under the radar as it generates less than 1% of the government’s revenue from extractive industries.

Global communities criticizing firms for doing business in Myanmar have tended to concentrate on the oil and gas sector, which resulted in the announced withdrawal of multinational energy firms TotalEnergies and Chevron from the now war-torn country.

In the absence of conversations about the pearl industry, Hsu Hsu, an official from the MEGGA Initiative, said pearl companies had become the quiet “abettors” of the Myanmar junta.

Revenue generated for the military

Most international companies in Myanmar operate pearl farms in the Myeik Archipelago, which provides a suitable habitat for the Pinctada Maxima oysters that produce golden South Sea Pearls, dubbed “the queen of pearls” due to their fineness and scarcity.

This saltwater oyster can take up to three years to cultivate between one and two pearls, while a freshwater oyster takes about six months to yield a dozen, making the South Sea Pearls rare and expensive.

Pinctada Maxima oysters are also sensitive to the environment. They can grow only in certain coastal areas like the Myeik Archipelago – now on a tentative list of UNESCO’s world heritage sites – Australia, Indonesia and the Philippines.

According to a report by the Nikkei Asia, South Sea Pearls have been spotted on many public figures, including Hillary Clinton and Aung San Suu Kyi, highlighting the esteem and affection many hold for these pearls.

This has attracted international companies to Myanmar’s coast since the 1950s, with the arrival of Japanese pearl farming operators. The industry grew after the 1990s when Myanmar started to open up and ended three decades of General Ne Win’s authoritarian era.

The pearl industry generates revenue for the current junta government through tax, application and license fees, and in-kind from overseas companies – which must share 25% of harvested pearls and transfer pearl cultivation techniques to the state-owned Myanmar Pearl Enterprise (MPE).

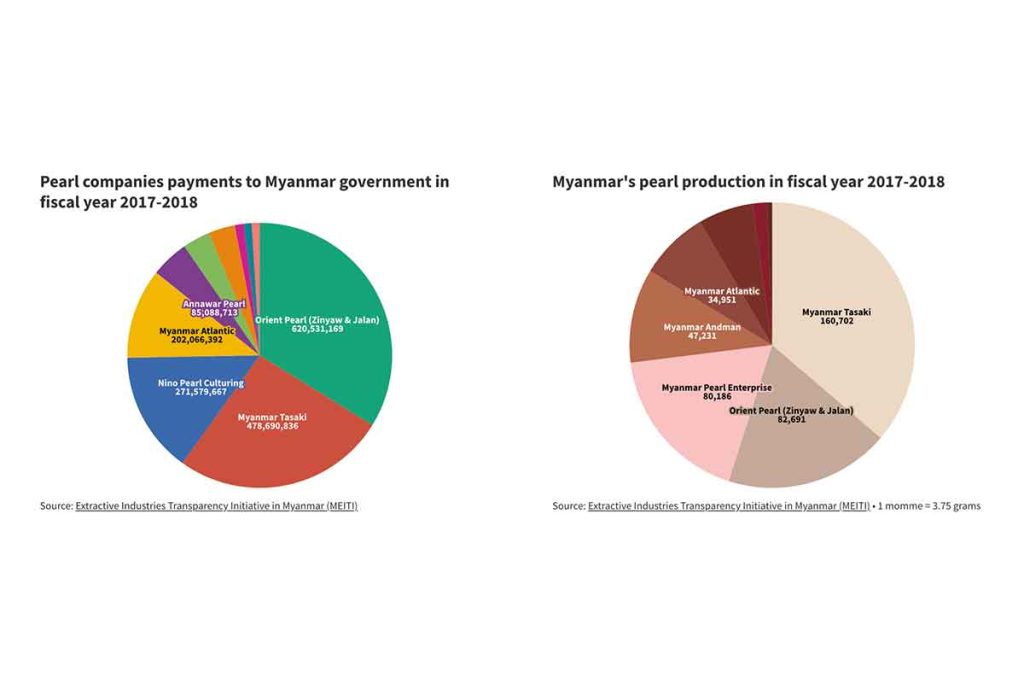

The most recent published data in a Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative report showed that 11 companies – four foreign and seven domestic – contributed 1.8 billion MMK (nearly $US1.3 million) to the government in the 2017-2018 fiscal year.

Of the four foreign companies granted permission for pearl farming, Myanmar Tasaki contributed the most, accounting for 26% of the government’s revenue from the pearl production industry.

This was followed by Australian joint venture Myanmar Atlantic (11%), Thailand’s Myanmar Andaman Co Ltd (3%) and Singapore’s Belpearl Myanmar Co Ltd (1%).

Myanmar Tasaki exported 75% of its pearl production, valued at about $6 million. This value can increase drastically when the pearls are turned into designer jewellery items in the luxury market.

Even before the military coup, the pearl industry was very controversial because its expansion into the Myeik Archipelago forced many indigenous Moken people to lose their homes, and it also affected local fisheries.

“The pearl farms in Tanintharyi region began their businesses by forcibly occupying the habitat of the Moken people,” said Mon*, a Moken rights activist. “They are still expanding in the eastern part of Domae Island after the coup, and they responded with no action [on the impacts on Moken communities].”

Business as usual

In April 2021, the United States Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control announced a sanction against MPE, the state-owned pearl company.

It stated that the pearl industry was among the “key economic resources” for the military regime that was “violently repressing pro-democracy protests in the country and that is responsible for the ongoing violent and lethal attacks against the people.”

Despite the sanction, the military government and MPE were able to conduct at least six gem auctions since the coup and sold more than 1,200 pearl lots with the minimum opening price for each pearl lot at $1,000.

The Irrawaddy reported that the recent auction was held in the capital Naypyitaw in October when 300 lots of pearls, 160 lots of gems and 4,025 lots of jade were offered. The finest jade was only sold in foreign currencies ranging from dollars to euros, yuan and baht – showing the high interest of foreign buyers.

This led the National Unity Government (NUG), Myanmar’s parallel government, to call on the buyers not to source gems produced under the military government and said it would act against the civil servants and companies participating in the auctions.

As the pearl businesses continue as usual, advocacy groups such as the Blood Money Campaign, Human Rights Now and Justice for Myanmar called on Tasaki to end all its business with MPE, while accusing Tasaki of supporting the junta by maintaining business links with the state-owned enterprise.

“Whether you are doing pearl businesses or buying pearls from Myanmar, you have to be aware that money from pearls is used against the people,” said Mike*, a member of the Blood Money Campaign. He also urged the Japanese people to monitor their government’s talk and work in Myanmar.

Tasaki replied in an email to Dawei Watch, saying “there are no commercial relationships including joint ventures between Myanmar Tasaki Co Ltd and the Myanmar military and other military-related organizations.”

It added that Myanmar Tasaki was a 100% owned local subsidiary, while it runs the pearl farms under a license in the designated sea area, the same as local and foreign pearl farmers.

“We consider the situation in Myanmar to be very serious, and we believe that any violence against the people is unacceptable. The safety, security and well-being of our employees remains our primary concern. We will pay the highest attention to the local situation, especially in our pearl farm area, and will take the best possible measures,” replied Tasaki.

“We hope to see a swift resolution of the current situation based on dialogue and reconciliation in accordance with the will and interests of the people of Myanmar.”

…………….

*Note: Pseudonyms are used in this story for security reasons.